(This essay was originally published March 25, 2014. The version below includes several minor corrections and updates.)

I’m in my therapist’s office, talking about friendship. I’ve been struggling with emotional intimacy and honesty—my whole life, actually, but it’s caused some more acute problems recently, which is why I’m back here now. In more practical terms, I’m here because my therapist is willing to schedule appointments via e-mail.

Last week we talked about how hard it is for me to articulate emotions, and how much I obsess over precision of language, and how closely that’s linked to how scared I am of miscommunication, of lying by the sheer act of trying to name something so personal and subjective and dependent on factors more complicated than any sentence or word or idiom can ever convey.

I’m a professional writer.

The irony is not lost on me.

Wolverine and Beast, Astonishing X-Men #18

My homework this week has been to look at the very few relationships in which I feel comfortable talking about my feelings—especially negative feelings—and find common factors.

The answer, once I stumbled across it, was so stupidly obvious that I cracked up, and then I spent half an hour writing it down and tweaking the phrasing so I could be sure that when I told him he would hear what I meant.

The common factor, I tell my therapist, is cultural frame of reference. The only way I am consistently comfortable communicating feelings is via broad fictional allegory. The friends who know me best—not just likes-and-dislikes-and-interests, but things more fundamental and less articulable; the friends I’m willing to let see me fucked up; the friends I text at 3 AM when my world is falling apart; are the friends who read the same comics I do.

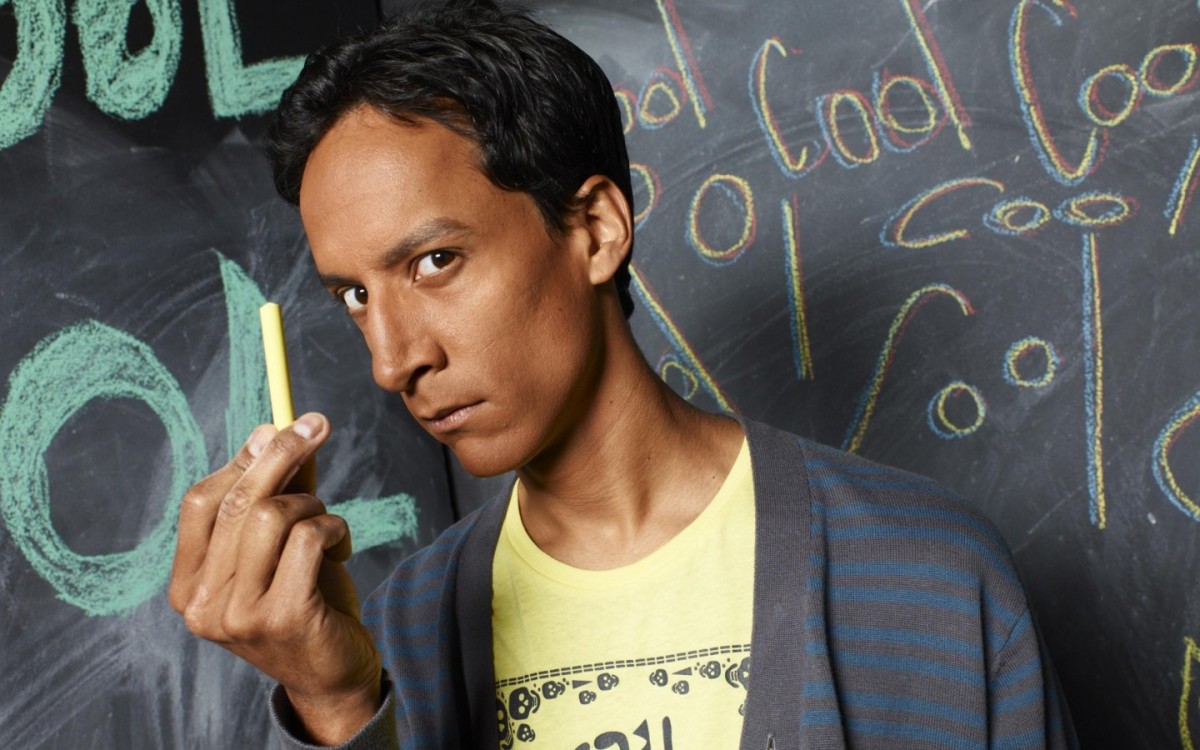

I tell him that I have a folder on my desktop labeled “feelings” that is mostly panels clipped from comics and Community gifs.

I tell him that I think maybe we should talk about Autism Spectrum disorders.

He tells me he’s been meaning to bring that up for a while now.

The Lady-Friend and I have been binge-watching Community. We love it a lot, for a lot of reasons, but Troy and Abed are our favorites. We have the kind of romantic relationship that is substantially goofy and involves a fair lot of best-bro grade-school-slumber-party nonsense; and while Troy and Abed are about ten years our junior, we are tickled as hell to see our very specific demographic of “adults who are still pretty into blanket forts” reflected in popular media.

Abed is my favorite character because Abed makes sense to me in a way that the other characters don’t. Abed is simultaneously exceptionally perceptive and exceptionally dense. Abed celebrates his interests in an obsessive, minutiae-focused way. Abed talks in pop cultural references and parses his experiences in general and interpersonal dynamics in particular by drawing parallels to the structure and terms of fictional storytelling—although when he does it, there’s an extra layer to the joke because he is, of course, a committee-written fictional character on a sitcom.

In the pilot of Community, early on, there’s this exchange: Jeff, the leading man, who’s kind of an asshole, says, “Abed, I see your value now,” and Abed, genuinely excited, answers, “That’s the nicest thing anyone’s ever said to me.”

I thought for a long time that the joke was that Jeff only saw people’s value when they were of direct use to him; that he thought he was being snide but actually saying something pretty nice. It turns out that the joke is that Abed interprets it as a compliment.

It’s often hard for me to tell when people are joking. It’s usually hard for for me to tell when they’re making fun of me.

I can’t imagine a more reassuring compliment than being told that someone sees my value.

I don’t tell my therapist this, but I do tell him about the Season 1 episode “Contemporary American Poultry,” in which the study group takes over the school as a chicken-fingers-themed crime family with Abed at the top.

Jeff likes being in charge, so he goes off to try to get Abed to stop. “The mafia movie is over,” he tells Abed.

And Abed, who has an organizational chart behind him listing everyone’s likes and needs, says, “I’m not doing a mafia movie. In fact, I don’t need to use movies or tv shows to talk to people anymore. Before, I only needed them because the day-to-day world made no sense to me, but now, everyone’s speaking the same language: chicken. I understand people, and they finally understand me.”

I thought, Yes. That makes perfect sense.

And then I thought, Man, that sounds so nice.

Cypher, X-Men: Necrosha #2

I like fiction, because fiction makes sense in ways that the real world doesn’t. Because in fiction, I have as much—more, often—interpretive resources as anyone else; because we’re all working from the same basic data set.

“I wish I were a fictional character,” I tell The Spouse, over and over, year after year. Fictional characters are fundamentally functional. They serve a purpose. If I were fictional, I would be of use. I could be everything anyone needs or wants me to be, with no self to get in the way. I could have a world with rules. I could be distilled into language, not lost again and again in imperfect translation.

The Spouse is extremely emotionally fluent. He’s all about those tight personal connections. He falls in love often and easily. He’s a feelings dude, and he uses words broadly and evocatively. He doesn’t get why I’d rather write about feelings than talk about them in person—to him, the personal contact and the connection are inseparable.

When I try to talk about how I feel—about things that matter—spontaneously, I trip over my own tongue. I drop out mid-sentence, go silent, trying to parse my thoughts. Eye contact distracts and panics me.

I’m fascinated by the way people interact, by the subtle languages of movement and physical cues and word choice and contact. I study it obsessively without ever quite managing to bridge the theory-practice gap.

Cyclops, X-Men: Prelude to Schism #4

I write out notes for important phone calls.

I write out notes for important conversations.

I practice facial expressions in the mirror.

I practice inflection in the shower.

I have never not done these things.

For a very long time, I assumed everyone did them.

I tell all of this to my therapist, and I also tell him that I’ve realized over the last few months that the experience I’ve always characterized as empathy is not, in fact, the same thing most of the people around me mean when they say “empathy.” Mine is more like very, very well-honed pattern recognition. I am a good listener. I give very good advice. I am very good at noticing and articulating patterns and motivations people don’t recognize in themselves.

I identify with very few of them.

Shadowcat and Cyclops, Uncanny X-Men #537

It’s not that I don’t care about other people. It’s not that I don’t have feelings, or that mine are somehow different. I think they’re probably the same as anyone else’s feelings, but I don’t interact with them in ways that make sense by the rubrics I’ve grown up learning, or the ones the people around me seem to apply.

Marvel Girl and Cyclops, X-Men: Season One

I have trouble with relationships in which I don’t feel like I’m of use—in which I don’t have something concrete to offer. I am much better at the explicit economy of professional relationships than the more nebulous territory of friendships. When it’s not explicit, I find it immensely difficult for me to eke out what’s expected of me.

Social rules don’t come instinctually to me; I look for patterns and cobble together crude rubrics based on them. In school, I got teased a lot, often under the loose pretense of friendship; as a result, I don’t really trust most people who seem to like me unless I can also discern a concrete reason that they’d value my company.

This clip is from Season 3, Episode 16 of Community, “Virtual Systems Analysis”:

They’re in the Dreamatorium, which is where Abed and Troy and now Annie play make-believe. The Dreamatorium is Abed’s territory—he’s the one who comes up with scenarios, makes the rules—but Annie, in a fit of pique, fucks with the cardboard engine so that instead of Abed’s imagination, it’s filtered through other people’s feelings and needs.

Abed interprets the result as a world without Abed.

This is a theme that will come up again. In Season 5, Episode 6, Abed screws up his budding relationship with a girl named Rachel. Near the end of the episode, he offers a “third-act apology,” complete with a pal providing the trope-requisite rainstorm via a watering can and stepladder. It’s a pretty recent episode, so I couldn’t find embeddable video, but here’s a screencap of Abed being sincere and damp:

And here’s the dialogue:

Rachel: Abed, this is adorable.

Abed: Just because it’s adorable doesn’t mean it’s not important. Listen. I’ve been accelerating our relationship because I’ve been worried I wouldn’t pass a lot of the tests. I wanted you to move in because I thought if Annie was around, I’d have less chance of screwing things up.

Rachel: You’re not screwing things up, though.

Abed: That’s good to know. But the problem with me will always be that I can never know for sure. There’s not a huge amount of people in my life that haven’t eventually kicked me out, and I don’t always see it coming. I don’t want it to happen with you.

Rachel: Well, don’t manipulate me and don’t keep secrets from me and we’ll probably be okay.

Abed: Cool.

Rachel: It stopped raining.

Abed: Yeah, it sure did.

Cyclops, Wolverine, and the Power Pack, X-Men and Power Pack #4

The pop-culture characters with whom I most closely identify—the ones in the panels and screencaps I employ as emotional surrogates—are Scott Summers, post-death-and-resurrection Doug Ramsey, and Abed Nadir.

Here are some things they have in common:

They’re outsiders. They don’t really—click—with the people around them, even when they’re central to organizations or storylines.

They’re bad communicators; or they’re good communicators in ways that serve them well under only very specific circumstances.

They’re bad at feelings and overwhelmed by intimacy.

They’re pedantic and precise.

They’re often demanding and difficult, and as often paradoxically socially naive.

They’re utility-oriented. They have trouble adjusting to or relaxing in scenarios in which they don’t fill a specific function.

They bond hard and fast. They’re fiercely loyal and protective—

—and they’re rarely the ones to leave.

Like Abed, I have trouble imagining a place for myself in any world not of my own making. I see other people’s tolerance of and interest in me as a finite resource, one I can renew to a limited extent by being of use, but which will eventually and inevitably run out. I have a long and serial history as a flavor of the month. I assume—based on precedent, although the individual countdowns can vary significantly—that most of my friendships are running on borrowed time.

I am aware of the things that make me an appealing companion. I’m very smart and passionate. I can be fun and whimsical and weird and wildly creative. I’m generous and loyal.

Shadowcat and Cyclops, All-New X-Men #18

I’m even more aware of the things that make me difficult to tolerate in more than limited doses. I’m too intense. I fixate: if we both love the Wachowski Speed Racer, I will be baffled when you don’t want to watch it again immediately, and again after that. You’ll realize that the eclectic-but-surprisingly-in-depth frame of reference that first impressed you is both badly uneven and the product of a compulsive tendency to get swept away in minutiae. My enthusiasm will go from charming to smothering. That smart, incisive analysis you admired will get in the way of your ability to just fucking enjoy things. What looked like whimsy will turn out to be weird and sometimes weirdly hostile compulsion and pickiness. The appeal of passion and conviction will be offset by extremely rigid ethical rubrics and a tendency to be ruthlessly judgmental and dismissive. I’ll goad you into arguments, and I won’t trust you unless you push back. You will realize that I am not scintillating when I don’t have the luxury of a delete key, or pithy without a forced character limit.When we talk, you’ll notice how often and how long I pause mid-thought. That I don’t really make eye contact. You’ll try to hug me, and your feelings will be hurt when I flinch.

You’ll realize that you don’t really know me as well as you thought you did, and you won’t really see a clear path from where you are to where you think the next landing ought to be. You’ll try to understand me, and I’ll push back, hard, like you’re trying to take something away. You’ll try to comfort me when I’m hurting, and I’ll either lie or run.

Cyclops, All-New X-Men #6

Many of these are not things I’m capable of changing. I know this because I have tried so hard, over and over, in every way I can find, nonstop, for thirty-one years. I can fake it, sometimes, but if you value genuineness and emotional intimacy, that’s going to get old, too.

Eventually, you’ll get fed up. You’ll leave. It’s okay. I probably would, too.

That’s why I keep you at arm’s length.

Cyclops, All-New X-Men #9

Well, it’s part of why I keep you at arm’s length. I’m not a people person.

People interest me. I care about some ferociously and passionately. I care about most in at least an abstract humanitarian sense.

But people also baffle and exhaust me, and I don’t trust most of them. They generalize and assume based on very limited data sets. They touch me. From behind. In crowds. They ignore the words I have so carefully arranged to say exactly what I want them to say and project their own insecurities and needs and prejudices. They treat me like an extension of them; they subsume who I am and what I say into whatever role they want or need me to fill and then punish me when I fail to follow a script I can’t see.

I wish I were better at being what people want me to be. I wish they’d tell me what that was.

I wish I knew what the rules were.

I wish there were rules.

“What you’re describing sounds a lot like the experience of someone with Asperger’s Syndrome,” my therapist tells me. I point out that according to the DSM-V, Asperger’s Syndrome no longer exists as a discrete disorder.

He laughs.

Cyclops, New X-Men #116

I’ve been reading about AS, and what I read resonates with eerie specificity. This makes sense in ways that attempts to parse myself almost never do. It’s like I had a huge volume of conflicting and confusing data, and suddenly, somehow, stumbled across the equation into which most of it plugs: Einstein making the connection between the transit of Venus and the theory of relativity.

Under the circumstances, the idea that there is a system that makes sense, even one that’s still theory at this stage, provides an intense but very tautological sort of relief.

We talk about diagnosis, and decide there’s no real reason to pursue an official one.

My therapist doesn’t do diagnostic testing, and it’s not a process I trust anyway: my last experience, in college, was grounds-for-a-complaint-to-the-APA horrific. An official diagnosis wouldn’t confer any real advantages: it’s not like AS is medicable; I function on a level that makes it highly unlikely I’d ever seek the kind of services that require an official diagnosis; and I’m self-employed, so reasonable workplace accommodations are kind of a moot point—my career is basically a reasonable accommodation. It’s also really, really expensive. And while I’m acutely aware of the cliche of semi-self-diagnosis, and the attendant baggage, it’s kind of a drop in the waterfall when it comes to social awkwardness.

Ethically, my therapist can’t say “probably” or “I suspect” in context of anything that sounds like a diagnosis, but he says that it seems like it would be a good idea to proceed as-if, which is good enough for me.

This is how I explain it to The Spouse:

“Imagine I’m a computer—I know, I know, just embrace the cliché—and we’re in a world where the overwhelming majority of computers run Windows, and we’ve all kind of always assumed that I’m just kind of buggy, because while a lot of things function the way you expect them to, some things don’t or require weird workarounds, and some things just don’t run at all.

“And then, imagine figuring out that oh, shit, I’m not a Window’s box. I’m a Mac with a Windows skin. And there’s enough UI overlap that people who go in assuming I’m running Windows will just assume that I’m buggy. And, again, there’s overlap—a lot of the functions and skills translate—but not all.”

My therapist likes the operating system analogy because it implies deviation more than dysfunction, which also fits with my read. The catch, though, is that disorder and dysfunction aren’t just intrinsic qualities: they’re also contextual. It doesn’t really matter how well your OS runs if you make up less than a tenth of a percent of the software market.

Cyclops, X-Men: Season One

This is what scares me: If this is real and right—which I’m fairly certain it is—there are probably things of which I’m fundamentally incapable.

I mean: there are plenty of things of which I’m fundamentally incapable. I am not ever going to be an elite athlete or the CEO of a fortune-500 company. But those are exceptional things. These are normal things—things most people assume to be universal. Things that are supposed to be universal.

I always assumed that if I tried harder and longer, if I approached those problems from enough different angles, someday something would click.

It’s frightening to realize that fake-it-‘til-you-make-it may not apply. That there might be functions I can’t replicate. That there are gulches that can’t be bridged.

I’m not usually a very jealous person, but the idea that there are common terms on which the Spouse and the Lady-Friend can relate to their other partners but not to me fucking wrecks me.

That I’ve come to terms with the idea of people leaving doesn’t mean I’m not also scared of being alone.

The Spouse and I have known each other since we were eleven. We’ve been together, in some form or another, for more than half our lives, and we’ve grown up shaped by that mutual proximity. We speak a common language of decades of shared experience and inside jokes; of the books over which we first made friends; of movies and games and comics; of our shared sense of humor, which is weird and oblique and so deadpan that other people sometimes have trouble picking up on it.

The Spouse is a sysadmin; when I tell him the operating-system analogy, he thinks for a minute. “No,” he says. “They’re Macs, and you’re running Linux.”

Oblique approaches and elaborate metaphor aren’t that intuitive for him, any more than feelings are for me—but he understands how much the precision of the analogy matters, even if he doesn’t quite get why.

This is how he explains:

“You’re not something totally foreign to other people: you’re based on the same core. Maybe your interface isn’t intuitive for most users, and you can’t run all the same software, but for someone willing to put in the time, you’re more versatile and better oriented for a lot of specific advanced functions and customization.”

This is what I hear: I see your value.

It’s the nicest thing anyone’s ever said to me.

I related to this article quite a bit, more than I suppose is comfortable.The use of fictional characters for reference and analogy is there, the not getting stuff everyone else just gets is an occasional struggle too. I seem to spend my life misunderstanding and being misunderstood, my wife and I do share a common language, half is our own idiosyncracies and the other is pop culture references and shared jokes that we get, but few others do. It was comforting to see thoughts and ideas I have kept to myself written down from someone else’s mind.

Thankyou for sharing this post and thanks for re-posting, since I wasn’t on wordpress to see it 2 years ago.

That’s another tick in the “I should watch Community” column.

I am glad you are not a fictional character, because you’ve value, probably to many more than you believe.

Cyclops smiling, there’s something you don’t see every day

I have a bit of an edge, there.

You are my new favorite human. Thank you for this.

[…] extent to which I’m overinvested in the X-Men in general, I am really overinvested in Scott Summers. As a critic, I can step back; as a fan, every piece of X-media lives and dies by the quality of […]

I very much enjoyed reading this article, and thank you for your willingness (and bravery) to be vulnerable in this sharing. We’ve only met recently and I haven’t gotten a chance to know you well, but I hope to get the chance to become actual friends at some point and not just karaoke buddies and FB friends.

I keep writing and erasing a comment because I keep rambling or getting too personal. This piece is important to me, Jay, and thank you very much for sharing.

I’m a huge fan and am extremely grateful for how much this has helped me understand a couple people who are very close to me that I care about deeply. Thank you, again.

Thank you. I struggle with words and the ability to express my difference. I am so excited to share the operating system metaphor with my partner when he wakes up. Thank you for giving me those words (and sharing your experiences).

Hi Jay, Today my therapist unofficially (similar to your own situation of diagnostic cost and availability) diagnosed me with mild Asperger’s disease or somewhat more officially, being high functioning on the Autism spectrum. It was like a light coming on unifying everything wrong with me my entire life. I’m thirty eight, and finally things make sense. I searched for Aspergers and came across your article. As luck would have it, I’m a huge fan of your Xplain the X-Men podcast. Anyway your article made me feel things and I don’t enjoy that. Anyway, you left me understanding, crying a little and thinking I just might be on a path to getting better. Thanks Jay

Dave

Aw, man, thank you, so much. If you’ve got any questions or are looking for resources, please feel free to drop a line.

Also, FWIW and if you’re interested, I’ve written a bit more about this specifically in context of the podcast over here: http://www.xplainthexmen.com/2015/06/spectrum-x/

Thank you so much for your nice comment and also for the redirect to the other article. I’m so new at realizing that I have Autism and that I’m not just horribly shy and social phobic. It’s been both empowering and hurtful. I particularly liked the part where you mention labeling someone as taking away their agency. That’s certainly how I have been feeling today. Thank you so much.

Dave

I found that it helped a lot to look at it less as removal of agency and more as gaining understanding. You’re not broken or fucked up; you’re just trying to run one system based on the manual for another. Connecting with other people on the spectrum and learning to navigate some of the things that just didn’t work when I’d tried to approach them before made a big difference, too. The challenge doesn’t go away, but it gets easier to see the value, too.

I’ve felt alone all my life. My brothers used to play with each others and their friends, but I just didn’t get it. Usually I just sat and read about stuff that I liked and, when someone tried to speak with me, I speaked obsessively about my favorite theme of the week. I never really get that conversation is less about what is being said than… I don’t know… About saying something? About agreeing? Really, I didn’t got it even now.

When I got older I’ve been diagnosed (?) as Asperger and I must say, it was kinda… Liberating, I guess? Feel that there is some people around the world that was somewhat like myself. Understand that, yes, I’m a mutant freak that never will quite understand normal people but the things that I can understand and do, well, they can’t either. I can see patterns in information that is completely oblivious to most people and I got a carreer thanks to that. It’s just like The Spouse (I don’t know why you’re calling him, that, but… ok) said: We are Linux. Not very friendly, but a hell of a system to process specific tasks.

Re: “The Spouse” – I published this article before Miles had any web presence outside of friends-locked social media, and I was (am) pretty obsessive about protecting other people’s privacy in my published work.

This is one of my favorite posts on the internet, no that isn’t a hyperbolic statement.

This is my second time reading this and it’s still so powerful and as an ASD person I relate so much.

Thank you for this.

this article explains my entire life experience better than i ever could

Similarly diagnosed in late 2014. Computer metaphor is just the one I need as I try to explain that I’m not broken and being autistic isn’t something I’d change. Hope your 2.5ish years of sorting life after the useful realisation have been Really Good.

This is EXACTLY how I feel about people – very well put. “People interest me. I care about some ferociously and passionately. I care about most in at least an abstract humanitarian sense.

But people also baffle and exhaust me, and I don’t trust most of them. They generalize and assume based on very limited data sets. They touch me. From behind. In crowds. They ignore the words I have so carefully arranged to say exactly what I want them to say and project their own insecurities and needs and prejudices.”

I thought this was fascinating. I read it from the perspective of having had two friends in my life, one diagnosed with Aspergers, and the other self-diagnosing and exhibiting some similar behaviours to the ones you describe. I love them dearly, but I struggle to get past the more challenging facets of their personality, as they possess a somewhat relentless nature.

Abed’s an interesting choice to focus on, as I found his character particularly annoying for the very reason he reminds me so much of people I know; I didn’t find Abed charming or funny, I found him tiring and a little close to home.

You’re clearly very, very self-aware, and you can write about it in a very precise manner. Does that come easily to you? The reason I ask is that I would only see this among my friends on very, very rare occasions; specifically once or twice in a decade, usually when times were bad. The rest of the time they’d overtly wear a persona which didn’t necessarily work very well for them; an evolved coping mechanism that didn’t mesh with most of the people close to them, socially and professionally, with the resulting friction.

I don’t know if we’re the same. Chances are good we’re not. But I do understand communicating with other people across what feels like a vast gulf. When I was freshly into my twenties, nearly a decade ago now, I remember making some remark about human nature that my family all agreed was genuinely insightful. I don’t remember what it was now, but I do remember replying, “Yeah. I understand humans pretty well. I’m just not any good at being one.”

At my worst, I depersonalized so badly, I remember referring to myself as being “More of a function, less of a person.”

Most of my fictional affiliations like you have with Cyclops are all…benevolent aliens, I guess? Really like the Doctor, Superman, people like that. Hyper-empathic non-humans are my jam. People with a genuine, deep love of humanity, but are forever apart from them too. Earnestness is my problem. I feel like other people express feelings through a tiny keyhole and every time I try to do that, it blows the whole damn door down instead. Everything I feel is five sizes too big. At some point, I just realized sincerity as I understood it was scary to other people. I learned to be an excellent liar. To talk a lot and say nothing. Writing is the only space that feels safe to unleash the full Phoenix Force (I almost ended that sentence with “if you know what I mean” and then thought: “You idiot. If any single being on earth was going to know what you meant by that, it would be Jay.”) So, the writing isn’t just my life, it’s how I can bear to be alive at all. It’s the only space where I can comfortably be all of me, just let it rip.

I’ve spent most of my twenties coming to grips with the fact that the pool of people that I can comfortably relate to is vanishingly small and there is a non-zero chance that I’ll die alone, despite how fiercely I love people. I think that’s Ok. It kind of has to be.

Anyway, I see your value. Sorry I wrote so much. Got carried away again.

I am not a writer. I am autistic. Thank you, thank you, thank you for putting words to so many pieces that hurt.

Hi, Jay–your article resonated strongly with me (I cried while reading it), and I felt compelled to write an essay in response. Would it be okay for me to post the response essay on my blog, with a link to, and quotes from, your article?

Yes, absolutely!

[…] particular, Edidin speaks about writing an essay titled, “I See Your Value Now: Asperger’s and the Art of Allegory,” which was about “the ways that I use narrative and narrative structures to navigate real […]

Barely got a page in, and I absolutely have to interject that I definitely see a potential value in you, Sir.

Downright Arthurian value, actually. I hope you’re good with rabbit holes. This is a long story.

https://davidiclineage.wordpress.com/2018/09/13/well-hi-there-im-dave-of-davidiclineage/

And now that I’ve finished, I’ll quit telling you Merlin’s story, and bring you right to the rock. That’s the center of gravity to which salience accords.

https://davidiclineage.wordpress.com/2018/09/08/newest-draft-davidic-legend/

[…] me go back a step: in 2014, I wrote and self-published an essay called “I See Your Value Now: Asperger’s and the Art of Allegory.” It was the first really personal piece I’d put online: a long exploration of the process and […]

The sign of me trusting a therapist (and my most intimate personal relations, come to think of it) is when I freely volunteer my thoughts about the fictional characters I relate to. I’m always glad to see there are other adults out there who use character analyses for similar purposes.

Thanks for this, Jay. I’ve been struggling to articulate very similar problems to my new partner. Reading this has helped me to more appropriately express my perspective of things being on the Spectrum to her.

Thank you for writing this and leaving it up until now. I saw bits of myself in your story, and the Linux metaphor was maybe the most loving description I’ve ever heard of the experience. I’m just now, in my mid 30’s, finding the framework for what I’ve been experiencing my whole life, and it can be hard to find adult narratives that resonate with the uncountable coping-skills I’ve developed to navigate my relationships and career. I’ve always enjoyed your writing, and I really appreciate that you continue to share your stories.

Not to trigger your “obsession with the accuracy of language,” or anything, but if you had such an obsession; I doubt you would be using the word “ironic” to describe the situation of someone obsessed with language becoming a writer; as this is not in any way the opposite of what one would expect. What one would expect is for that person to be on the correct side of one of the most common linguistic missteps in the entire English language. So, incidentally, this situation right here is actually ironic.